1

Bénédicte Meillon, 2014

Les procédés de traduction

(cf Paillard et Chuquet 11-39,

Françoise Grellet 124-29

Jean-Paul Vinay et Jean Darbelnet, « A Methodology for Translation », in The Translation Studies Reader, ed. by Laurence Venuti )

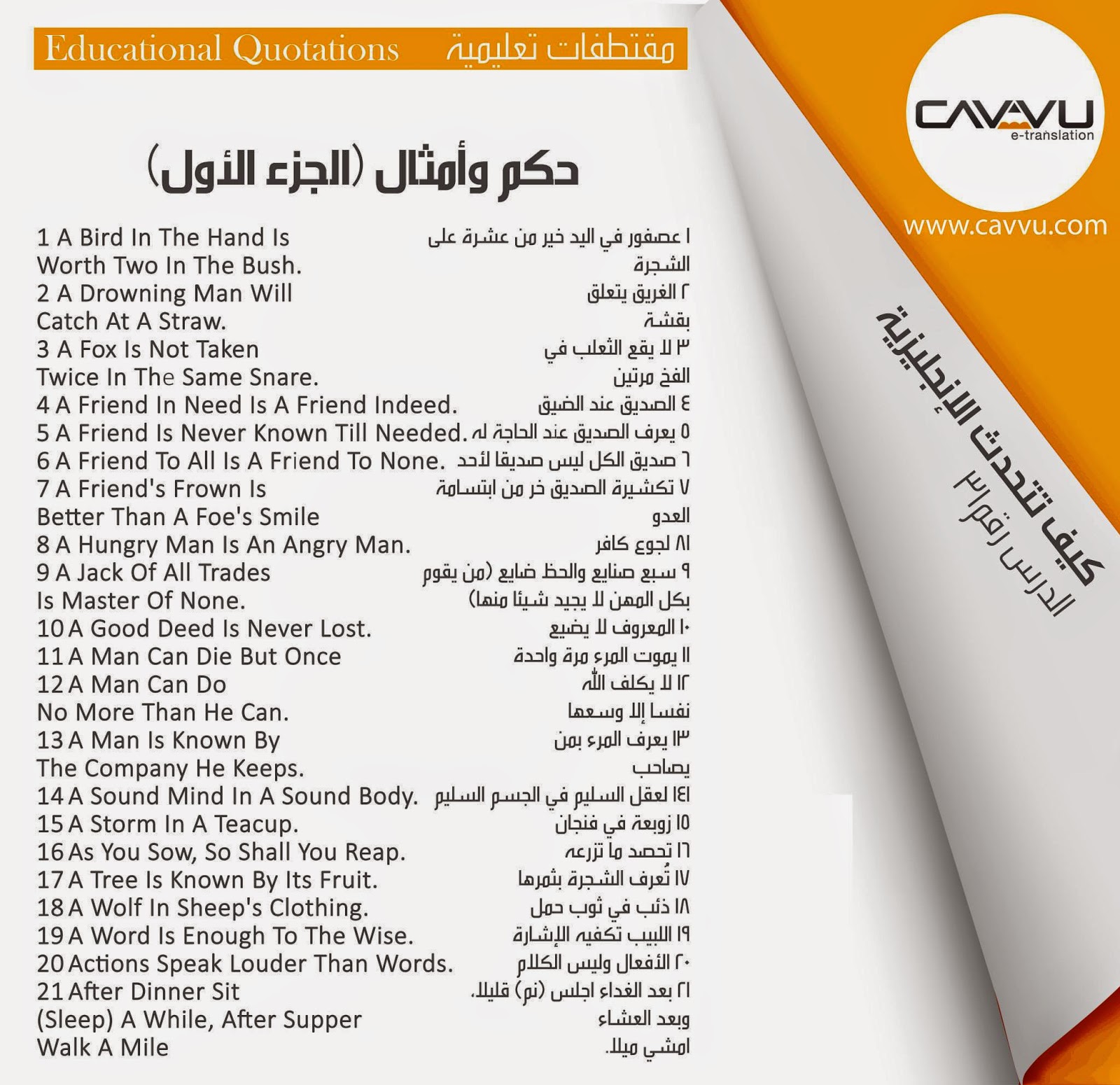

1. L’emprunt

Au niveau du lexique, emprunté à l’autre langue :

Ex : Bulldozer, dollar (emprunté de l’anglais) et fuselage, chic, déjà-vu (angl., emprunté du français ).

Budget/Internet (français, emprunté de l’anglais.).

Attention aux faux amis : « rendez-vous », qui rajoute une connotation amoureuse, ou tout au moins l’idée de flirt (le mot « flirt » étant un autre cas d’emprunt) en anglais (pas le même sens que « appointment », pour un RV chez le médecin ou avec le banquier par exemple).

2. Le Calque

Une structure est calquée sur une langue et restituée telle quelle dans l’autre langue. Le résultat ainsi obtenu n’est donc pas en accord avec les règles syntaxiques habituelles de la langue d’arrivée. On parle de gallicisme et d’anglicisme selon le sens dans lequel le calque a été effectué.

Ex : Lutétia Palace (fr.) et Governor General

Science-fiction : science fiction.

Cela peut bien entendu être une source de mauvaise traduction, à partir du moment ou le calque ne correspond pas à un usage déjà établi (je ne peux pas dire « la rouge voiture » pour « the red car »).

3. La traduction littérale

Traduction mot à mot.

Ex : Quelle heure est-il ? :: What time is it ?

The train arrives at Union Station at ten : Le train arrive à la gare Centrale à dix heures.

Où êtes-vous ? Where are you ?

2

4. La transposition

Lorsque l’on remplace une catégorie grammaticale par une autre, sans changer le sens de l’énoncé : Un syntagme verbal devient un syntagme nominal, un auxiliaire modal (e.g. may) est traduit par un adverbe modal (e.g. peut-être) etc.

Ex : I will tell him as soon as he arrives. Je lui dirai dès son arrivée.

He may be there already. Il y est peut-être déjà.

As soon as he gets there…. Dès son lever…..

NOM VERBE

Priorité à droite Give way

For sale À vendre

L’appareillage eut lieu à l’aube They set sail at dawn

Is this your first visit ? C’est la première fois que vous venez?

ADJECTIF NOM

Medical students Des étudiants en médicine

Le premier ministre britannique Britain’s Prime Minister

Attempted murder tentative de meurtre

Ses soupçons n’étaient pas fondés His suspicion had no foundation

ADJECTIF VERBE

People are suspicious les gens se méfient

Disponible avec notice d’usage…………… comes with full mounting instructions

ADJECTIF ADVERBE

An occasional shirt for Garp de temps en temps une chemise pour Garp

Ce dernier, agacé, répliqua replied huffily that

ADVERBE VERBE

I still think that Je persiste à penser que

He merely nodded Il se contenta de hocher la tête

Dans le temps, il y a avait un café à cet endroit There used to be a pub here

Est-ce que par hasard vous savez… ? Do you happen to know… ?

3

PREPOSITION VERBE

She hurried into the church Elle se dépêcha d’entrer dans l’église

I went down the wide stairs, through Je descendis l’escalier et traversai

the rooms to the bar. les pieces pour arriver jusqu’au bar.

ADVERBE PROPOSITION

She plainly preferred to… Il était évident qu’elle préférait

Russia predictably did not like….. Il était à prévoir que la Russie…..

Kindly address your remarks to me Vous êtes priés de vous addresser

directement à moi pour tout remarque.

5. Le chassé croisé (cas particulier de transposition)

Lorsque l’on a à la fois un changement de catégorie grammaticale et une permutation syntaxique des éléments sur lesquels est réparti le sémantisme. Procédé le plus fréquent dans la traduction des verbes anglais suivis d’une préposition ou d’une particule adverbiale, notamment les phrasal verbs. On le rencontre le plus souvent pour traduire les verbes décrivant un déplacement :

The young woman is walking briskly away. La jeune femme s’éloigne d’un pas

court et rapide

He groped his way across the room Il traversa la pièce à tâtons

He swam across the lake Il traversa le lac à la nage.

Don’t worry, it’ll wash out Ne t’inquiète pas, cela partira au lavage.

6. L’étoffement (cas particulier de transposition)

Lorsqu’on introduit un syntagme nominal ou verbal pour traduire une préposition, un pronom ou un adverbe interrogatif. Parfois employé aussi lorsqu’il y a simple « dilution », par exemple lorsqu’une préposition est traduite par une locution prépositionnelle :

The wreck was found off Land’s End. On a retrouvé l’épave au large de Land’s End.

Ex d’étoffement :

I picked up the magazine from the stack on the table: Je pris un magazine dans la pile

qui se trouvait sur la table.

7. La modulation

Implique un changement de point de vue, une fçaon diffrénte de se représenter quelque chose :

4

Instant coffee café soluble

Lost property office bureau des objets trouvés

- dans une description spatiale :

She had drenched her skirt from the knees down :: Sa jupe était trempée jusqu’aux

genoux.

- passage de l’abstrait au concrêt:

He’s always using words a yard long :: Il emploie toujours des mots qui n’en finissent

plus.

- Affirmation/ négation :

His attendance record was not very good Il avait été fréquemment absent.

It is not difficult to show….. Il est facile de démontrer que….

She’s rather plain Elle est sans grande beauté

- Une partie pour une autre, ou pour le tout :

There he was at his desk, his head bent over his work :: il était là, assis à son bureau, le front courbé sur son travail.

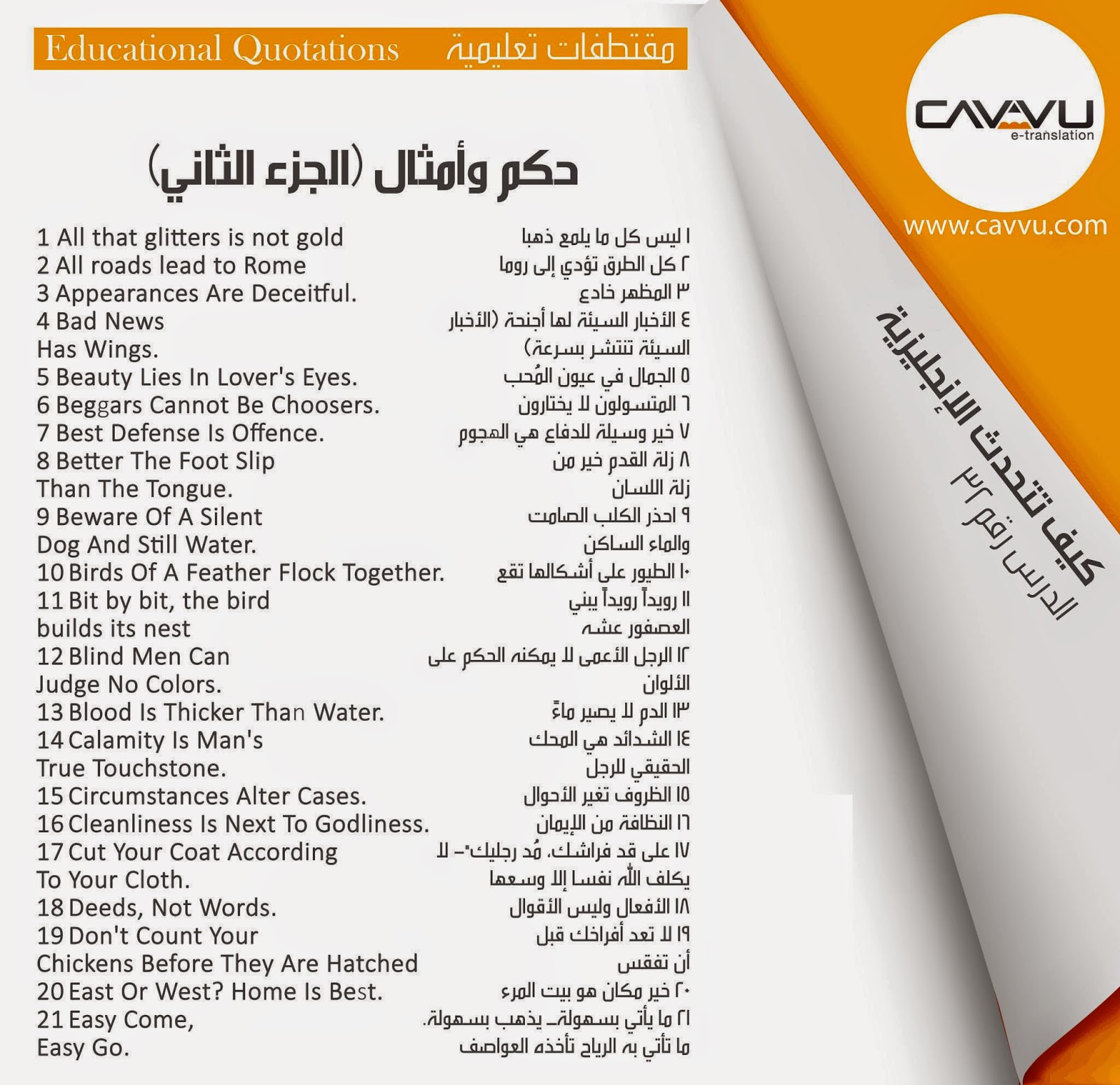

8. L’équivalence

Lorsque une expression ne peut être traduite que par équivalence (ex les proverbes, certaines expressions idiomatiques, expressions figées) :

You’re welcome ! Avec plaisir/ de rien !

Medium rare, please. A point.

Rare Saignant

Well done. Bien cuit

Comme un chien dans un jeu de quilles. Like a bull in a china shop.

It’s raining cats and dogs. Il pleut des cordes.

En un clin d’oeil Before you could say Jack Robinson

Cela concerne également les bruits que font les animaux

Cocorico cock-a-doodle-do

Miaou miaow

Hi-han heehaw etc.

5

9. Adaptation

On recourt à l’adaptation dans des cas extrêmes, lorsqu’aucun autre procédé ne peut être utilisé, le plus souvent pour traduire des situations ou des réalités (culturelles par exemple) qui n’existent pas dans la culture cible. C’est un procédé très fréquent dans la traduction des titres de film et d’oeuvres littéraires notamment.

Jaws. Les dents de la mer.

Shallow Grave. Petit meurtre entre amis.

Dans certains contextes : Baseball (sport national). Cyclisme.

Attention toutefois à ne pas systématiquement assimiler toute réalité culturelle de la langue d’origine à un équivalent plus ou moins égal sur le plan culturel de la langue cible. Il faut tout de même réfléchir aux questions d’identité culturelle, aux dangers de l’assimilation, et à l’ élan potentiellement nationaliste ou impérialiste qui peut sous-tendre l’adaptation et la traduction.

A noter : certaines traductions peuvent mettre en jeu plusieurs procédés à la fois. La traduction de Jaws par Les dents de la mer relève de l’adaptation d’un titre (« Les mâchoires » serait un titre à l’évidence moins accrocheur), mais aussi de la modulation du point du point de vue par synecdoque. La traduction DEFENSE D’ENTRER par PRIVATE (affiché sur une porte par exemple) représente à la fois un cas de modulation (on affirme que l’espace derrière la porte est privé, ou bien on en interdit l’entrée), de transposition (l’adjectif est traduit par un groupe nominal), et d’équivalence (il s’agit d’une expression figée). Idem pour la traduction de « saignant » pour la cuisson de la viande par « rare » : il s’agit bien entendu d’un cas d’équivalence, mais qui entraîne en même temps un changement de point de vue. Ces changements de point de vue sont intéressants en eux-mêmes, et ils renseignent sur les différentes façons dont la langue influe sur nos façons de nous représenter le monde. La traduction littérale de « saignant » par « bloody », en plus de risquer d’être mal interprétée sur le plan du registre (de par la valeur de juron de l’adjectif « bloody » en anglais ; comme dans la plaisanterie, si l’on commande un « bloody steak » à un serveur anglais on risque de se voir proposer : « How about some f***ing potatoes to with it ? ») engendre une modulation du point de vue qui pourrait choquer un anglophone, qui, dans sa langue, n’a pas l’habitude de se représenter de façon aussi crue, c’est le cas de le dire, le caractère sanguinolent de la viande dans la cuisson à la française.

- Enseignant: Dr Samir ERRAHMANI

- Enseignant: Dr Samir ERRAHMANI

Research Methodology is a course designed to equip second-year students with the essential tools to navigate the world of academic inquiry. Specifically, this course guides the students through science of research within the field of English as a Foreign Language. It focuses on methodologies, from qualitative to quantitative approaches, enabling students to critically analyze, design, and conduct research projects. Through engaging lectures and practical exercises, students learn to formulate research questions, gather and evaluate evidence, and craft compelling arguments using scholarly sources. The main aim of the course is to enable students to explore, interrogate, and contribute meaningfully to the ever-evolving landscape of English studies through rigorous and systematic research practices.

- Enseignant: amina aissaassia

- Enseignant: safia chibani

- Enseignant: safia chibani

- Enseignant: safia chibani

How to Be a Good Translator?

Translation is a highly skilled, rewarding and satisfying job. But how can we become a good translator?

One of the most experienced translators in the world; Lanna CASTELLANO; has described the translator’s career path as follows:

“Our profession is based on knowledge and experience. It has the longest apprenticeship of any profession. Not until thirty do you start to be useful as a translator, not until fifty do you start to be in your prime.

The first stage of the career pyramid –the apprenticeship stage– is the time we devote to investing in ourselves by acquiring knowledge and experience of life.

Tips for translators:

Here are some tips that might help in order to be a good translator:

1. Love language, especially your own. And keep studying it.

2. Learn to write well.

3. Learn about and study your passive language and the culture it comes from.

4. Only (Generally) translate into your own language.

5. Select a specialist area of expertise, and study and be prepared to learn more about your specialist subject. Constantly.

6. Read: books, newspapers, blogs, magazines, adverts, style guides, cereal packets…

7. Listen: to TV, the radio, friends and family, strangers in the street, on the bus, in bars, in shops…

8. Attend workshops, seminars and conferences in your subject area – listen to the experts, absorb their language. Even their jargon – but try not to use it.

9. Keep up with current affairs.

10. Keep your I.T skills up-to-date.

11. Practise and hone your skills – keep up with your training.

12. Listen to the words that you write (some writers and translators read their texts out loud to themselves). Languages each have their own rhythm. If your writing doesn’t “sound” right, try changing the word order, not just the words.

13. Use your spell-checker. Use it judiciously, but use it. Always.

14. Print out your translated text and read it on paper before delivering it to your client. Always. Especially if you use computer-assisted translation (C.A.T) software. Print it out.

15. Ask yourself if your translation makes sense. If it makes you stop, even for a second, and think “what does that really mean”?, then there’s something wrong.

16. Write clearly and concisely, using the appropriate sentence -and paragraph- length for your target language. Use simple vocabulary. You can convey even complex ideas using clear, straightforward language.

17. Inform your client of any mistakes, typos or ambiguous wording you find in the source text.

18. Find ways to add value for your clients.

19. Always keep your reader in mind.

As you’ve probably noticed, most of these tips also apply to writers, not just translators. After all, translation is a form of writing, and good translators should be good writers too. The important thing is to practise and hone your skills. And always use your brain. That’s what makes a good translator a reallygood translator.

- Enseignant: Dr Samir ERRAHMANI

La traduction en tant que science, ayant forte relation avec la linguistique du fait qu’elle traite les langues étrangères (spécialisées) et dans son acception principale de traduction interlinguale est le fait de faire passer un texte rédigé dans une langue (« langue source », ou « langue de départ ») dans une autre langue (« langue cible », ou « langue d'arrivée »). Elle met en relation au moins deux langues et deux cultures, et parfois deux époques.

الترجمة على وزن فعلل مصدرها "ترجم" , وجمعها "تراجم" , والتاء والميم أصليتان.وجعل الجوهري التاء زائدة و أورده في كتاب "ر جم" و يوافقه في نسخة ما في نسخة من التهذيب من باب "رجم" أيضاً.

ولها في اللغة أربعة معانٍ:

1- الترجمة تعني سيرة الشخص وحياته. فنقول مثلاً " قرأتُ ترجمة فلان " أي قرأت سيرته".

2- الترجمة تعني التحويل, فيقال مثلاً " أرغب أن تُترجم الأقوال إلى أفعال" أي " أرغب أن تتحول الأقوال إلى الأفعال"

3- الترجمة تعني نقل الكلام من لغة إلى أخرى.فقولنا " ترجمة النص العربي إلى الإسباني" ,أي " نقلت كلام النص من اللغة العربية إلى اللغة الإسبانية".

4- الترجمة تعني التبيان والتوضيح.و"ترجم فلان كلامه" إذا بيّنه و وضحه.

Hunayn Ibn Ishaq, ou Abū Zayd Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq al-'Ibādī (v. 808–873), est un médecin syriaque de Bagdad, de religion chrétienne nestorienne, connu par ses traductions d'ouvrages grecs, notamment médicaux, vers le syriaque, la langue de culture de sa communauté religieuse, et l'arabe, sa langue maternelle. Il était surnommé le « maître des traducteurs ».

الترجمة عند الغرب

يعود تاريخ الترجمة عند الغرب إلى ترجمة التوراة السبعونية، التي تعدّ أوّل ترجمة للعهد القديم من العبرية إلى الإغريقية. عمل على ترجمتها سبعون أو اثنان وسبعون مترجما، إذا أرسل كبير الكهنة في اسرائيل آنذاك ، المترجمين إلى الاسكندرية بناء على طلب حاكم مصر، لترجمة التوراة لصالح الجالية اليهودية الموجودة في مصر والتي لم يكن بمقدورها قراءة العهد القديم بلغته الأصلية، العبرية. اصبحت هذه الترجمة فيما بعد الأساس لترجمات أخرى، فقد ترجمت فيما بعد إلى اللغة اللاتينية والقبطية والأرمينية والجورجية واللغة السلافية.

الترجمة عند العرب

العرب كانوا يرتحلون الى التجارة ويتأثّرون بجيرانهم إذ احتكّ العرب بالفرس والرّوم والأحباش ومن الصّعب قيام مثل هذه الصّلات دون وجود الترجمة، ازدادت الحاجة الى الترجمة فترجمت عن اليونانية علوم الطب والرياضات والفلسفة وتطور ذلك في عهد الخليفة هارون الرشيد وابنه المأمون الذي أسّس دار الحكمة.

ترجمة كتاب كليلة ودمنة الذي هو مجموعة أمثال وحكم على السنة الحيوانات ألفه بالسنسكريتية الفيلسوف الهندي بيدبا وهداه للملك المستبد دبلشيم، ترجمه ابن المقفع في 750 م في عهد الخليفة ابي جعفر المنصور من الفارسية الى العربية.

يقول الجاحظ لا بدّ للترجمان ان يكون بيانه في نفس الترجمة في وزم علمه في نفس المعرفة أن يكون أعلم الناس باللغة المنقولة والمنقول اليها حتى يكون فيهما سواء وغاية.

أنواع الترجمة

أورد Jakobson ثلاثة تقسيمات للترجمة، نوردها فيما يلي:

النوع الأول، ويسمى بالترجمة ضمن اللغة الواحدة intralingual translation. وتعني هذه الترجمة أساسا إعادة صياغة مفردات رسالة ما في إطار نفس اللغة. مثل عمليات تفسير القرآن الكريم.

النوع الثاني، وهو الترجمة من لغة إلى أخرى interlingual translation. وتعني هذه الترجمة ترجمة الإشارات اللفظية لإحدى اللغات عن طريق الإشارات اللفظية للغة أخرى. وهذا هو النوع الذي نركز عليه نطاق بحثنا. وما يهم في هذا النوع من الترجمة ليس مجرد معادلة الرموز ( بمعنى مقارنة الكلمات ببعضها ) وحسب، بل تكافؤ رموز كلتا اللغتين وترتيبها.

النوع الثالث، ويمكن أن نطلق عليه الترجمة من علامة إلى أخرى intersemiotic translation. وتعني هذه الترجمة نقل رسالة من نوع معين من النظم الرمزية إلى نوع آخر دون أن تصاحبها إشارات لفظية، وبحيث يفهمها الجميع. ففي البحرية الأمريكية على سبيل المثال، يمكن تحويل رسالة لفظية إلى رسالة يتم إبلاغها بالأعلام، عن طريق رفع الأعلام المناسبة.

وفي إطار الترجمة من لغة إلى أخرى interlingual translation، يمكن التمييز بصفة عامة بين قسمين أساسيين:

1- لترجمة التحريرية Written Translation :

وهي التي تتم كتابة. وعلى الرغم مما يعتبره الكثيرون من أنها أسهل نوعي الترجمة، إذ لا تتقيد بزمن معين يجب أن تتم خلاله، إلا أنها تعد في نفس الوقت من أكثر أنواع الترجمة صعوبة، حيث يجب على المترجم أن يلتزم التزاما دقيقا وتاما بنفس أسلوب النص الأصلي، وإلا تعرض للانتقاد الشديد في حالة الوقوع في خطأ ما.

2- الترجمة الشفهية Oral Interpretation :

وتتركز صعوبتها في أنها تتقيد بزمن معين، وهو الزمن الذي تقال فيه الرسالة الأصلية.

إذ يبدأ دور المترجم بعد الانتهاء من إلقاء هذه الرسالة أو أثنائه. ولكنها لا تلتزم بنفس الدقة ومحاولة الالتزام بنفس أسلوب النص الأصلي، بل يكون على المترجم الاكتفاء بنقل فحوى أو محتوى هذه الرسالة فقط.

ثانيا: الترجمة التتبعية Consecutive Interpreting :

وتحدث بأن يكون هناك اجتماعا بين مجموعتين تتحدث كل مجموعة بلغة مختلفة عن لغة المجموعة الأخرى.

ويبدأ أحد أفراد المجموعة الأولى في إلقاء رسالة معينة، ثم ينقلها المترجم إلى لغة المجموعة الأخرى

لكي ترد عليها المجموعة الأخيرة برسالة أخرى، ثم ينقلها المترجم إلى المجموعة الأولى ... وهكذا.

ومن الصعوبات التي يجب التغلب عليها في الترجمة التتبعية، مشكلة الاستماع ثم الفهم الجيد للنص من منظور اللغة المصدر نفسها.

ولذلك فيجب العمل على تنشيط الذاكرة لاسترجاع أكبر قدر ممكن من الرسالة التي تم الاستماع إليها.

ثالثا: الترجمة الفورية Simultaneous Interpreting :

وتحدث في بعض المؤتمرات المحلية أو المؤتمرات الدولية، حيث يكون هناك متحدث أو مجموعة من المتحدثين بلغة أخرى عن لغة الحضور.

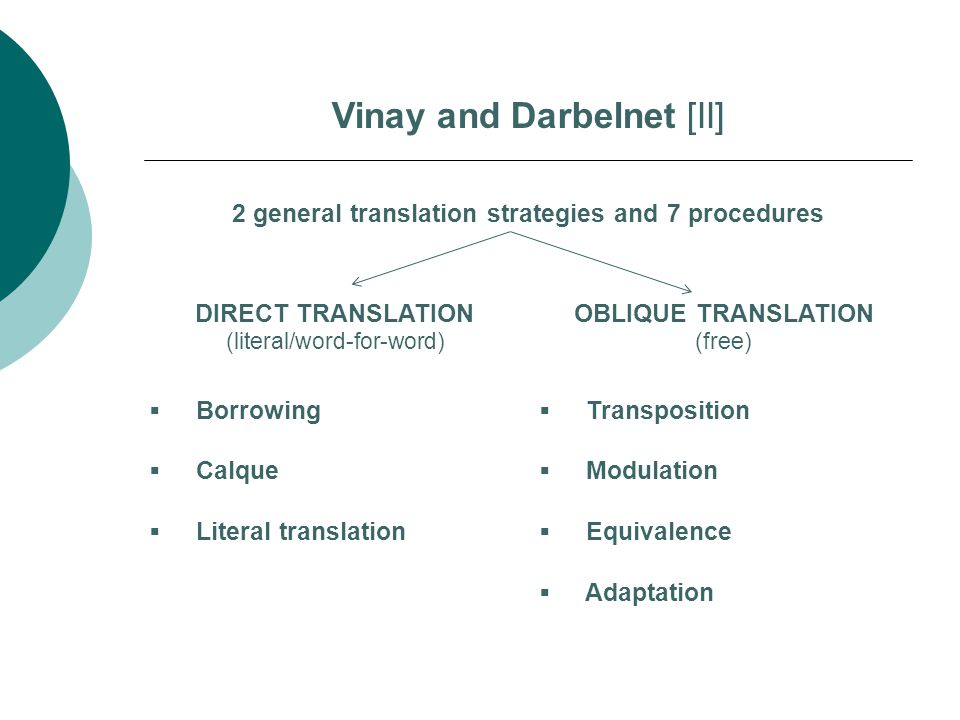

Jean-Paul Vinay, Jean Darbelnet

Stylistique comparée de l’anglais et du français, Paris, Didier, 1966, pp. 46-55.

Procédés techniques de la traduction

1. Emprunt

2. Calque

3. Traduction littérale

4. Transposition

5. Modulation

6. Equivalence

7. Adaptation

1. Emprunt

lexique de l’informatique (hard disk, computer, mouse )

2. Calque

Le calque est un emprunt d’un genre particulier : on emprunte à la langue étrangère le syntagme, mais on traduit littéralement les éléments qui le composent.

لعب دورا: Jouer le rôle

يعمل كمدرّس: Il travaille comme professeur

3. Traduction littérale

Traduction mot à mot

|

Il paraissait l’image de la santé |

كان يبدو صورة الصحّة |

4. Transposition

Une partie du discours est remplacée par une autre sans changer le sens du message.

He ran across the street / il traversa la rue en courant

5. Modulation

Variation dans le message obtenu en changeant de point de vue, d’éclairage.

|

Il est facile de démontrer |

It was not difficult to show |

6. Equivalence

Les moyens stylistiques et structuraux sont différents.

Revenir bredouille / رجع صفر اليدين

7. Adaptation

Si dans la situation ne peut pas être parfaitement entendue, alors il est nécessaire de faire recours à l’adaptation.

Brown butter / beure doux

Geroges MOUNIN, problemes theoriques de la traduction

Mathieu GUIDERE, introduction à la traductologie

- Enseignant: Dr Samir ERRAHMANI

Dr HAMDANI Yamina L2

Oral communication module

Simple but efficient life hacks to improve oral communication

1. Take Some Mental Notes

2. Use the mirror to practice speech

3. Read fiction literature

4. Listen to audiobooks

5. Get rid of filler words

6. Work on turning passive vocabulary into active

7. Take notice of your body language

8. Watch public speaking

9. Use varied dictionaries

10. Speak confidently

11. Become an active listener

12. Play word table-top games

1. Take some mental notes

Preparing and thinking over your speech in advance is always a good idea. Try to write down the thesis of your speech to structure it and highlight the main issues.

If you are planning to speak in front of an audience, make a communication plan for your speech on paper. For each item, I recommend writing down the main theses.

To make it easy, you can use note taking apps with stylus to record important information when preparing or just to memorize words.

2. Use the mirror to practice speech

One of the best ways to boost oral communication is just to spend several minutes a day standing in front of a mirror and talking. Pick a topic, set a timer for 2-3 minutes, and just talk.

The essence of this exercise is to watch how your mouth, face, and body move when you speak. You may feel as if you are talking to someone, so imagine that you are having a conversation with your workmate.

Talk for 2-3 minutes. Do not stop! If you stutter, try to rephrase the thought. You can always look up the word you forgot. Therefore, you will understand exactly what words or sentences you have difficulty with.

3. Reading fiction literature

Do this not only to enjoy the plot and emotions but also to improve your speaking skills. It is important to read books written in ornate literary language, paying attention to grammatical constructions, new words, epithets, and metaphors used for description.

Careful text analysis and its further retelling will help better understand and remember literary techniques, use them more naturally in spontaneous speech, develop your speaking skills, and expand your vocabulary.

Considering the number of metaphors, epithets, and outstanding grammatical structures, I would advise reading books such as ‘The Blind Assassin’ by Margaret Atwood, ‘Cloud Atlas’ by David Mitchell, and ‘The Shadow of the Wind’ by Carlos Ruiz Zafón.

Note: In accordance with Statista research, almost 90% of graduates in Mexico stated that oral communication played a big role in their careers. This further emphasizes that your oral communication skills can boost morale and productivity, and promote teamwork.

4. Listen to audiobooks

In my opinion, this point could be combined with the previous one, but reading printed and listening to audiobooks is significantly different. While listening to books, you can not only learn to speak more competently and replenish vocabulary but also pay attention to intonation, pauses, logical stress, timbre, and tempo.

Professionally recorded audiobooks can be a real treasure trove of useful information for those who want to stop talking monotonously and inexpressive. After all, the effect produced depends not only on WHAT is said but also on HOW it is pronounced.

Intonation can convey mood, feelings, and thoughts. Don’t believe it? Try to pronounce one word with different intonation and feel the difference. You can also use free text to speech software to listen to audiobooks, which can help you improve your pronunciation and intonation. Intonation can convey mood, feelings, and thoughts.

5. Get rid of filler words for better oral communication

Filler words are very common and difficult to eradicate. They spoil oral speech and sometimes, instead of delving into the essence, you focus on “like”, “well”, “so”, and “believe me”.

Finally, you even begin to perceive them as literary words that are inherent in the speech of an educated person. Actually, it’s a pity that an interlocutor will associate you with remembering these extra words.

Filler words live in spontaneous speech not as separate units, but as “substitutes”. People use them when it is hard to choose the right expression and they need to immediately fill a pause.

They cover the “gaps” in the story, but they really interfere with listeners. To find and eradicate filler words in your speech, you can record your voice and listen to it.

However, thinking about how to improve oral communication skills in practice, you should start with thinking over a system of penalties, when for each uttered “like”, “well”, “so”, “believe me”, etc. you will need to do something useful (learn a new word or do 5 squats).

Pro tip: After getting rid of the filler words, you need to train constantly, coming up with a variety of tasks. Choose an object and try to give it the most informative and coherent description within 5 minutes. Come up with a topic and express your thoughts using properly built grammatical constructions, metaphors, and epithets.

6. Work on transitioning passive vocabulary to active

Try to replenish your spontaneous speech with not only common words/phrases but also rarely used ones. Search in memory for terms, synonyms, and epithets.

However, make sure you are not misleading an interlocutor or bragging about your education. It lies in learning to speak clearly and coherently, using a rich vocabulary to clarify the wording, more capacious conveying of meaning, and avoiding misunderstandings.

Here is such a paradox – to expand the vocabulary and introduce new expressions into your speech, trying to simplify it.

7. Take notice of your body language

Although body language is a nonverbal communication method, it has a huge impact on how you convey information. Getting your audience interested in listening to you is not difficult – relax, keep your arms uncrossed, and your body at ease.

Other best ways to boost oral communication through body language involve making eye contact and maintaining good posture. To draw the audience’s attention to the necessary points, try to use gestures and facial expressions.

However, don’t go overboard, as excessive gestures can look comical and feigned, which means they will distract listeners from your message.

8. Watch public speaking

On the way to improve your oral communication skills, it’s also useful to refer to other people’s lectures, as well as films and performances, and observe the use of nonverbal ways of communication.

It’s a good exercise to watch movies with the sound off when you need to understand without words the story presented and the character’s feelings.

I used to watch TED Talks, created by pro-level speakers. These videos are a great way to hone your skills, and with subtitles in over 100 languages, they are available to everyone. Thus, you can not only learn new words but also see how to hold your audience and be confident during the speech.

Pro Tip: To practice facial expressions and gestures, I recommend training in front of a mirror. It’s even better to record your speech on video and then analyze it. Typically we can’t see how others perceive us, so it will be useful to look at ourselves through their eyes.

9. Use varied dictionaries

Don’t forget about explanatory and spelling dictionaries. There is no shame in referring to them to find a good word or making sure that it is pronounced correctly. Nowadays all of them are mobile-friendly allowing you to find a word in just a couple of taps.

How to improve oral communication skills using different dictionaries? Make learning one catchphrase your morning routine, and try to use it properly throughout the day. This greatly contributes to the development of spontaneous speech.

Calendars with new words, dictionaries of epithets and metaphors, synonyms, and antonyms are no less useful. Try not just to learn new words but also to use them as often as possible.

Regular training will make you a confident and interesting speaker and your speech more competent and exciting. You will notice how easy it will become for you to speak in front of an audience, and controlling your speech will turn into a habit.

10. Speak confidently for good oral communication

None of the methods will work without your self-confidence. If you don’t believe what you’re saying, listeners feel it and don’t believe it either. Your listeners should trust you and be interested in what you dwell on.

To demonstrate your confidence, there are plenty of tricks. They relate to your perception of yourself, intonation, etc.

The most universal is to prepare the outline of your future speech. It can be both written and mental, as you prefer. It is not necessary to compose a whole scenario of a speech – just define the main theses.

With the help of such notes, you will define the direction of your interaction with the audience and the key aspects of a conversation.

11. Become an active listener

Being a good listener is just as valuable as being a good speaker. Listening is an integral part of synchronous communication. To get started, remember the five steps of active listening:

- Receive

- Understand

- Remember

- Evaluate

- Respond

By following these simple rules, you will show your interlocutor that you are sincere and interested in what he is saying. By summarizing everything that has been said and asking clarifying questions, you will endear the interlocutor and achieve common ground faster.

12. Play word table-top games

I advise you to pay attention to those games that develop memory and replenish vocabulary. There are “Hangman”, “Scrabble”, “Chalkboard Acronym”, etc. allowing you to get wants and needs met.

During the game, each participant can learn many new words and their meaning, remember something from passive vocabulary, and show quick wit and ingenuity.

By downloading the game to your smartphone, you can have a great time while waiting or on the road. If a game is made for a team, involve your friends or even strangers to meet new people and practice communication.

Bonus: handy tips and exercises for improving articulation/dictation

To improve oral communication and spontaneous speech particularly, you can try various life hacks:

- Read aloud and with expression to train a good rate of speech, correct intonation, and rehearse facial expressions and gestures.

- Don’t be afraid to involve experienced teachers and attend public speaking training – a specialist can give good advice and correct mistakes.

- Practice spontaneous speech more often – even if it is difficult and scary, nothing will work without practice. At first, not everything may be very rosy, but the voice, speech apparatus, and diction will develop gradually.

- Sing frequently to improve your voice and develop intonation flexibility.

- Get acquainted with interesting people with a well-defined speech, discuss new performances and books, listen to them, and communicate with them.

Where to start improving oral communication?

The ability to speak vividly and competently is what distinguishes good from the best. By learning how to improve your oral communication skills and making strides in this, you will see how your personal and professional life will change.

By constantly honing your speaking and listening skills, you will open new doors. Good conversational skills will positively affect your relationships with your team, superiors, and clients. I think this article will come in handy for speakers, bloggers, actors, and just people striving to present themselves in all their glory.

Holtgraves, T. (2005). Social psychology, cognitive psychology, and linguistic politeness. Journal of Politeness Research, 1(1), 73-93.

Huang, D., Leon, S., Hodson, C., La Torre, D., Obregon, N., & Rivera, G. (2010). Preparing students for the 21st Century: Exploring the effect of afterschool participation on students' collaboration skills, oral communication skills, and self-efficacy. CRESST Report 777. National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST).

Hullman, G. A., Planisek, A., McNally, J. S., & Rubin, R. B. (2010). Competence, personality, and self-efficacy: Relationships in an undergraduate interpersonal course. Atlantic Journal of Communication,18(1), 36-49

Jones, Christopher, R., Fazio, Russell, H., & Vasey, Michael, W. (2012). Attentional control buffers the effect of public speaking anxiety on performance. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(5), 556-561.

Kishon-Rabin, L., Taitelbaum, R., Tobin, Y., & Hildesheimer, M. (1999). The effect of partially restored hearing on speech production of postlingually deafened adults with multichannel cochlear implants. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 106(5), 2843-2857.

Markow, W., Hughes, D., & Walsh, M. (2019). Future skills, future cities: New foundational skills in smart cities. Business-Higher Education Forum. Business-Higher Education Forum.

Martin, N. A., & Brownell, R. (2011). Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test-Fourth Edition (EOWPT-4). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Martin, R. C., & Slevc, L. R. (2014). Language production and working memory. The Oxford Handbook of Language Production, 1-33.

Mol, S. E., & Bus, A. G. (2011). To read or not to read: A meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 137(2), 267-296.

Mumtaz, S., & Latif, R. (2017). Learning through debate during problem-based learning: An active learning strategy. Advances in Physiology Education, 41(3), 390-394.

- Enseignant: yamina hamdani